How ‘Feminist’ Foreign Policy Will Change the World

March 15, 2022

Co-author Rollie Lal – Associate Professor of International Affairs, George Washington University

Co-author Shirley Graham – Director, Gender Equality Initiative in International Affairs and Associate Professor of Practice, Elliott School, George Washington University

Translator/Translator: Doan Thi Ngoc -Teacher-Lecturer-Hoa Sen University (HSU)

The Biden administration has a female Vice President, Ms. Kamala Harris, who holds the second highest position in the White House, and at the same time, 61% of women are also appointed to the White House.

Now, they have declared their intention to “protect and empower women around the world.”

Gender equity and the gender agenda are two components of “feminist foreign policy” – an international agenda that aims to dismantle the systems of diplomacy, immigration, defense, trade, and a male-dominated foreign aid system that has neglected women and minorities around the world. Feminist foreign policy reframes a country’s national interests, moving them away from military security and global domination toward equality as the basis of a peaceful and healthy world.

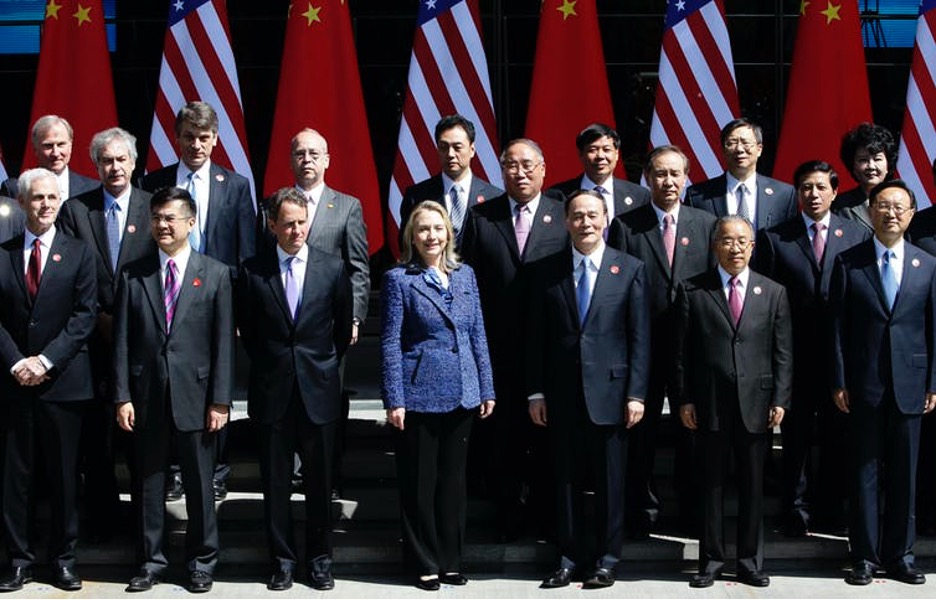

This is consistent with Hillary Clinton’s groundbreaking 1995 declaration at the United Nations, “ Women’s rights are human rights.”

The world could change in several positive ways if more countries, especially a power like the United States, made a concerted effort to improve women’s rights abroad, gender, and security scholarship like has been mentioned. Research shows that countries with more gender equality are less likely to experience civil war than other countries. Gender equality is also linked to good governance: Countries that exploit women are more unstable.

Women are not yet a top priority in any country’s foreign policy. But at least more and more countries are starting to put them on the agenda.

WOMEN ARE AT THE BOTTOM

In 2017, Canada launched a “feminist international support policy” to support women, children and adolescent health around the world.

To fulfill its promise of financial allocations until 2023, Canada pledged to provide C$1.4 billion to governments and international organizations annually, to enhance access to access to nutrition, health services, and education for women in developing countries. About $700 million of this money will go toward promoting sexual and reproductive health and rights and eliminating gender-based violence. About $10 million over four years will go to UNICEF to reduce female genital mutilation.

In January 2020, Mexico became the first country in Latin America to adopt a feminist foreign policy. This strategy aims to promote gender equality internationally; combat gender-based violence worldwide; and confront inequities across all social and environmental justice sectors and programs.

Mexico must also increase its Foreign Ministry staff to at least 50% women by 2024 and ensure it is a violence-free workplace.

Neither Canada nor Mexico achieved their lofty new goals.

Critics say Canada’s lack of focus on men and boys leaves traditions and customs that support gender inequality insufficiently addressed. And in Mexico, which has the highest rate of gender-based violence in the world – where 11 women are killed every day by men – it is hard to see how a government cannot protect its women. can credibly promote feminism abroad.

But at least both countries explicitly take women’s needs into account.

FEMINIST FOREIGN POLICY

The United States has also taken steps toward a more feminist foreign policy.

In the summer of 2020, under the Trump administration, the Departments of Defense, State, and Homeland Security, along with the U.S. Agency for International Development, each announced a plan to include women’s empowerment. on their agenda.

These documents – adopted under the 2000 United Nations Security Council resolution on women, peace, and security – promote women’s participation in decision-making in conflict zones, promoting women’s rights and ensuring their access to humanitarian assistance. They also include provisions that encourage American partners abroad to similarly encourage women’s participation in peace and security processes.

These are the components of a feminist foreign policy. But the plans are still operating without consistent and continuous sharing, linkage, and coordination with each other. A truly feminist foreign policy would unite aid, trade, defense, diplomacy, and immigration – and always prioritize equality for women.

One of Biden’s initial moves when he took office in January was to rescind the “global gag rule” – a Republican policy that prohibits overseas medical providers from receiving any aid. of the United States to provide abortion-related services – even if they use their money. Studies show that funding constraints reduce women’s access to all types of health care, making them vulnerable to disease and forcing women to resort to unsafe abortions.

Reallocating financial resources in ways that level the playing field for women is another important aspect of feminist foreign policy. But again, it needs to be a consistent and consistent policy, not a one-time decision.

AFGHANISTAN, WOMEN AND PEACE

The United States, long a leading world power, is unlikely to replace its international military security strategy with a purely “feminist” foreign policy.

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

As evidence grows that women’s well-being is central to everyone’s well-being, the link between gender equality and global security can be naturally incorporated into global strategies. The updated demand focuses on traditional American goals such as international security and human rights.

Afghanistan demonstrates the need for – and opportunity for – a feminist foreign policy for the United States.

Afghan women suffered brutal discrimination under the Taliban, with girls banned from education and women barred from political, security, and business leadership roles. Currently, under the Afghan government of President Ashraf Ghani, 28% of Afghan parliamentarians are women and 3.5 million girls are in school. Women worry that their freedoms could be infringed in any power-sharing agreement with the Taliban.

Yet US officials have conspicuously, and controversially, failed to include gender issues in negotiations with the Taliban to end the war in Afghanistan. Only one U.S. negotiator is a woman – underrepresenting a country to say it is committed to protecting the rights of Afghan women. The Taliban delegation had no women and only four women sat in the 21-member delegation of the Afghan government.

With U.S. help, an Afghanistan accord could secure the gains women have made since the United States ousted the Taliban in 2001 – or it could sacrifice them for “peace.”.

The Conversation newspaper and author Rollie Lal and author Shirley Graham allowed Gendertalkviet to translate into Vietnamese and post the full text. On behalf of the Gender Talk Editorial Board, we would like to send our sincere thanks to the Author and The Conversation Newspaper for allowing us to republish the full text. The contributions of The Conversation Newspaper and the author are very valuable and meaningful.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Gender talk website: https://gendertalkviet.blogspot.com/2021/12/chinh-sach-oi-ngoai-nu-quyen-se-thay-oi.html